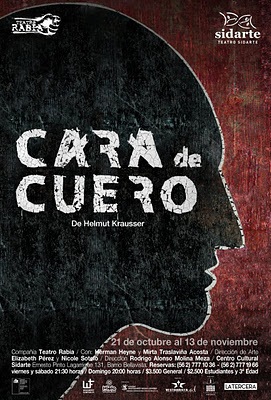

In 1994 the German writer Helmut Krausser (poet, novelist, short-story writer, playwright, and chess player) published his first dramatic text: Lederfresse (Leatherface). It is supposed that before it he had written a score of works and burned all of them.

‘Lederfresse’ has been staged since then more than a hundred times in many countries and has generally caused a great impact. The story is based on a true event: in 1987 the young Werner Bloy was murdered by the police in Munich. What was the reason? Bloy had a chainsaw in his house, he was wearing a leather mask sewn by himself and a costume like the killer of the famous movie "The Texas Chainsaw Massacre" (1974). The police, confusing reality with fiction, shot the young man to "save the life" of the woman with whom he was locked up, who eventually turned out to be his girlfriend. Later it was estimated that he was apparently preparing a performance.

On stage, two characters, a man who dresses like a serial killer and a woman who is a little bit drunk, drift between extreme emotional states: They switch from the deepest anger to an absolute delirium, and then to passion or tenderness. The space is suffocating, but the outside seems terrifying.

Both the ravings of the characters and the atmosphere of fear are successfully achieved by the Rabia Theater Company's proposal. The first relies mainly on the rhythm of the protagonist Herman Heyne, who plays a character full of nuances and achieves something that is hard to find: he turns a difficult, heavy and at times extremely poetic text into something close and even natural. Mirta Traslaviña, on the other hand, has a task on her shoulders which she carries out with grace, to be the rational voice, although a little drunk, lacking in that other character, who looks like a stupid, idealistic, and cool.

Secondly, the atmosphere, achieved through a visual proposal that suffocates despite being minimalist due to the existence of an object that cannot leave anyone indifferent: a chainsaw which at least disturbs the audience, being in front of such a ferocious instrument. Finally, the slight but unavoidable smell of gasoline which emanates from the famous device deepens the sense of confinement and sordidness of the proposal.

‘Cara de Cuero’ arrives to our billboard dealing with quality and irony both in the public speech of security as well as “The Normal” and the police work. (Yesterday, today and always, in Germany 1987 or Chile 2012).